Visualizing the Richmond Slave Trade

Robert K. Nelson, University of Richmond

Maurie McInnis, University of Virginia

American Studies Association, San Antonio, November 2010

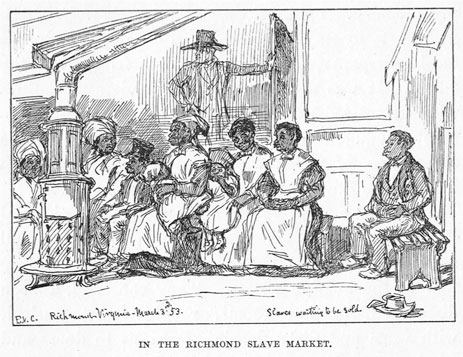

In March 1853, English painter Eyre Crowe visited Richmond. Having recently read Uncle Tom's Cabin, on his first morning in the city Crowe promptly located some advertisements for slave auctions in a local paper, asked someone at his swanky hotel for directions, and set off to witness the slave trade firsthand for himself. He didn't have to travel far--just a few blocks--before he located the nucleus of Richmond's slave trading establishments on Wall Street. He witnessed one auction, moved a bit down the road to another auction house to witness a second, and again to a third. In that third room, he took out paper and pencil to sketch a group of slaves waiting to be auctioned. Drawing these enslaved men and women rather than buying them was a suspicious and provocative thing to do. Fearing he might be an abolitionist, the dealers and buyers in the room soon threatened Crowe. While, by his own account, he didn't immediately flee lest he betray cowardice, he did display common sense; he soon if unhurriedly left, making his retreat from Richmond's slave district.

Crowe's encounter with Richmond gives the historian opportunity to think about how the slave trade was arrayed in-and how it, in fact, produced-urban space. Henri Lefebvre has reminded us that spaces are produced by societies through practices intimately linked with production and reproduction. In the case of Richmond, the slave trading district combined these purposes: reproduction of African Americans was itself economic production, and the physical network of this sprawling market was the material representation of that space. These spaces were in turn interpreted through "representational space," works of art and text that flow out of a political and economic order and give meaning to the spatial practices and representations of that order. In the short time we have this evening, I would like to show how an English painter, standing outside a slave society, imagined the spaces of the slave trade as they were being destroyed; to hint at how black Richmonders developed new practices on the rubble of the slave trade, and how a collaborative team at the University of Richmond and the University of Virginia have begun thinking about those spaces today and how we represent them one hundred fifty years after the fact.i

But first, back to the Richmond Eyre Crowe saw. It was a crowded, unordered, messy, place. Today in Richmond, like downtowns in medium-sized cities throughout the US, buildings are often large, monolithic structures that rise above the streets. Blocks that in the 1850s, 60s, and 70s held fifty or sixty distinct structures today are home to a single large one, bearing witness to the intertwined consolidation of corporations across nation-states and across local cadastral maps.

In the middle of that Richmond-not at the center of the main commercial strips, mind you, but in slightly marginal spaces, adjoining cooperages, wagon repair establishments, and in the basements of fine hotels-one found the slave trade. In some ways, the off-center placement of the trade testified to the odd place it held in Virginia culture. The slave trade was far and away the state's largest industry and Richmond among its most heavily trafficked nodes. More than 80,000 men, women and children were forced from the state in the 1850s, down from the 1830s, when about 120,000 were taken, or the 1840s, when Virginia sent out nearly half of all enslaved people in the US being forced across state lines. Richmond's share of this total is difficult to measure directly, but the ledger from just one slave trader gives some sense of scale: in the 1840s, he sold about two thousand slaves each year.ii

As central as the trade was to the state's economy, the trade itself was not as openly celebrated in the state's political culture or literature as it was in other parts of the South. Most often, white Virginians did not mention enslaved people at all, and when they did, they were mentioned in ledgers. When mentioned by name, enslaved women, especially, were placed in the context of domestic sentimentality-the space of familial reproduction, through which white writers obscured the productive role black women played, both through their labor and their labor pains. The spaces of the slave trade mapped on closely to the texts of the slave trade-central, but hidden, pervasive, but just out of sight.iii

In some of Crowe's early sketches, we see conformity to the representational aesthetics of his day: "In the Richmond Slave Market" shows men and women mostly quiescent, sitting with their hands folded, mostly wearing smiles. Crowe's sketch differs greatly from many abolitionist sketches of the trade mainly in its lack of interest in the traders themselves-the trader here literally has faded into the hatched shadows-or in emphatically locating sin within the site of the slave trade. That Crowe was making the slave trade visible at all would be interesting indeed if he had attempted to publish his sketch in the U.S. But this sketch was for the London Illustrated News.

- iHenri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1991) 33. [back]

- iiPhilip Troutman, "Slave Trade and Sentiment in Antebellum Virginia," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 2000) 419-421; Michael Tadman, Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South (Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 64. [back]

- iiiOn slavery as domesticated in southern texts, particularly those generated in Virginia, see Troutman (2000). [back]